- Home

- Jeannette Angell

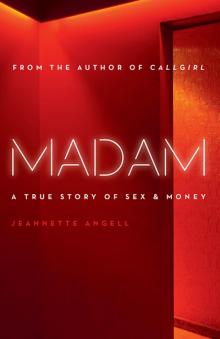

Madam Page 16

Madam Read online

Page 16

Once I made an appointment for her to see a client out in the suburbs. I arranged for a car taking another one of the girls who was calling on another client in the same town to drop her off first. The other girl finished her call and came back to pick up Jill, only to find that the client wanted to extend his time another hour. “Only if you’ll see both of us,” she told him, pouting prettily; and so he agreed, and ended up with the two of them for an additional two hours.

Now, I’m not saying that I couldn’t have arranged the same deal, but Jill did a lot of my work for me.

When she saw a client she liked, she never hesitated to pressure him into booking her again, right away, on the spot. “I’m free tomorrow night, shall we say eight o’clock?” she’d say as she was getting dressed, and before he knew what had happened I’d be calling him to confirm the appointment. Maybe it was the Israeli Army thing, I don’t know, but I can’t remember any guy saying no to Jill, not even once.

Hell, they said no to me, all the time.

I’d book her on busy nights for three calls in a row and she’d still be wanting more. I wondered what she did about freshening up between those calls, since I had drivers taking her directly from one to the next, but no one was complaining. The truth is that she was making me a lot of money and I wasn’t about to look too closely at how she did it. I was pretty sure that she wasn’t cheating or stealing clients from me. For one thing, she didn’t have the time; I was keeping her so busy. For another thing, I always know when one of the girls tries to steal a regular. He may be infatuated with someone in the short term, but in the long term his real relationship is with me, and he knows it. I’m part mother confessor, part dominatrix. They always come back, begging for forgiveness, sounding like cheating husbands as they plead the weakness of the moment and promise to never, ever, ever do it again.

And just like any other cheating husband, they will. So I make them pay for it for a while by having them see girls no one wants to see, and then I forgive them, and the whole cycle starts up again, repetitive and predictable. So much for the glamour of it all!

I didn’t think that Jill was stealing clients—at least, not regularly enough to counterbalance the prodigious amount of money she was bringing in. I also knew it wasn’t going to last very long. No one sees clients at that rate for any sustained period of time: they all burn out. The ones who last are the ones who pace themselves. Margot only went on calls on weekends; Jen, after a few months in the business, only went on one call on any given evening; Cam only saw clients if she had already had a good workout that day. And they lasted. With people like Jill, I always think that three months is the cutoff point. You can do anything for three months. Beyond that lies burnout, and I watch for that, because it’s when you’re burned out that you make mistakes. Oh, maybe not the kinds of mistakes that make you want to register your DNA with the local police; but mistakes all the same. And I don’t want them happening on my watch.

A month went by, and Benjamin and I bought a new dining room set. It was hard for me to imagine when something like that would rock my world, since takeout on the coffee table had always been my norm until then. I didn’t even have a dining room in my old apartment in Bay Village. Now here we were with this gorgeous wrought iron and glass table, these tapestry chairs, and they were there in large part thanks to the income I was getting from Jill.

The first hint of trouble came, as it always does, from the clients themselves. John Richter called me one evening and asked for a call, and I said that Jill was available.

“Um, Peach, that’s okay. Is there anybody else?”

“Why, John, what’s wrong?” Because I knew there was something. John was sweet and easygoing, and I don’t think that he had ever before in the four or five years I’d known him rejected anybody I’d sent to him.

He cleared his throat. Twice. That had to be a bad sign. “It’s just that—oh, Peach, it’s okay. It’s probably just me. You can send Jill.”

“No, John, if there’s a problem, I need to know about it. Please tell me.”

Another throat clearing. “Well, it’s not like it’s anything bad, you know. I think that maybe I’m wrong, maybe it’s my imagination or something …”

Just get on with it, I thought impatiently. “I’m sure it’s not,” I soothed. “Listen, this is my business. It’s important to me that you’re happy. You’d be doing me a huge favor if you’d help me here.”

A deep breath. “Well, you know, she never actually asks for a tip—“

She’d better not, I thought savagely.

“—but she makes you feel bad if you don’t give her something extra, you know?”

“I have absolutely no idea what you’re talking about,” I said.

John was floundering. He was a lawyer, I remembered irrelevantly. I devoutly hoped he wasn’t this much at sea when he was in front of a jury. “Um … well … she hints,” he managed to blurt out. “She never says anything outright, but she makes you feel like you have to do what she’s hinting at.”

“Like what?” I didn’t know if I was fascinated or repulsed.

“Like, you know, I said I was going to get tickets to the Boston Pops, and she made me feel like I should get her some at the same time. So I did.” He sounded shamefaced, as well he should. Jill was showing an unanticipated turn of enterprise here. “Go on,” I said grimly. There had to be more.

“Well, that’s it, really. I mean, there’s other stuff …”

“What kind of stuff?” He was making me pull teeth, and I was suddenly angry with Jill, for making this nice ordinary man feel so bad.

“Well, I mentioned that I was buying some new dishes, so she let me know … she made me feel that I should give her my old ones.”

“John, I’m sorry,” I said helplessly.

He was on a roll. “Then there was my Gretzky jersey,” he said, plaintively. “My brother-in-law had it signed for me … ”

“John, I’m appalled—“

“and some of my mother’s jewelry. She wanted to try it on while we were—um—having sex, you know, and I told her she looked so good in it—and she did, Peach, really, it was all flashy and brilliant on her, and I said she could borrow it, and she said no, she’d be too afraid she’d become too attached to it to return it, so of course I said …”

Of course you did.

“And then she had this friend who didn’t work for you, who didn’t want to work for a service, but Jill had told her about me and she really wanted to do a double with Jill, so I said yes.”

Yikes, it was getting me where I lived now. “John,” I said, firmly, to stem the torrent, “John, thank you for telling me. Jill won’t come by to see you tonight. In fact, Jill won’t be seeing anyone anymore.”

“You can’t do that!” he yelped.

“Why on earth not?” I’d have thought it was exactly what he wanted.

“She’ll know it was me,” he spluttered. “She’ll know I told you, Peach, and she knows my phone number, she knows where I live, she knows where I work—“

Why did she know where he worked?

“I took her there once, you know, when I had her over for a couple of hours. We did it on the desk.” He sounded embarrassed, and I pictured the high ceilings and sweeping views of the building on the waterfront where I knew he worked. “And maybe even introduced her to my partner once, I can’t remember …”

He was backpedaling. Not only had he introduced her, she was now seeing the partner—I would have bet my last dollar on it. That wasn’t stealing a client, technically, if I was correctly understanding Jill’s way of thinking.

“And I know she’ll be mad, I just know that she will …”

Whoa, Nellie. This successful fifty-something attorney, partner in an important Boston practice, doesn’t want to make a twenty-one-year-old precollege student mad at him? “John, I won’t tell her that you spoke to me at all.”

“She’ll know!” There was a rising note of hysteria in his voice. “S

he’ll know it was me, Peach, I swear she will!”

“Don’t be silly,” I said briskly, in my best no-nonsense nanny voice. “John, listen to me. Listen to me. You have to get a grip. I’ll talk to some other people, okay? You know that if this was happening with you, it was happening with other people, too.” If he had been in front of me, I would have slapped him across the face to wake him up. “John? John, are you listening?”

“Yes, Peach,” he murmured meekly.

“I will not tell Jill that you and I spoke. I’ll talk to some other people and then I’ll talk to her and I swear that she will not come after you. But you know that you should have told me this a very long time ago.”

“I know, Peach.”

“Okay. It’s all going to be all right.” I took a deep breath. “In the meantime, I’m going to send Sarah over to see you tonight, as a special treat. She’s gorgeous, blonde, slim, and she’s thinking about going into law. I know that you’ll have a good time.”

“Okay, Peach. Thank you.”

“It’s my pleasure, John.” I hung up the phone and thought, I’m going to kill that girl.

A Romantic at Heart

Jill was going to resurface. They always do, especially the ones about whom you have mixed feelings.

In the meantime, life goes on. I hate firing people and do it only when absolutely necessary. In a world where connections are everything, you don’t want to sever too many of them. So I let her go into whatever oblivion she had gone into. I’d deal with her later. I wanted to deal with my personal life for a while.

If you asked me to say, off the top of my head, where my favorite place in the world is, I’d have to reply that it’s Block Island. If you’ve not heard of it, that’s just fine with me, though someone, somewhere, called it one of the last great places in America.

When I first moved to Boston and was going to Emerson, some cycling enthusiast friend talked me into taking a day trip there. “We’ll rent bikes when we arrive. It’ll be great,” she assured me. I was enchanted by the ferry ride, a lot less enchanted by the cycling. (I’m not averse to exercise, but I’d rather be moving through clear water than up a dusty hill in the hot sun.) I looked at the old Victorian hotels lining the waterfront and felt a tug back in time, to an era of elegance and beauty, where afternoon tea was served, croquet was played, and people still dressed for dinner. I fell in love with Block Island then and have never fallen out of love with it since.

I nearly went there with Jesse once, but he bailed at the last minute and I stayed home alone and got drunk instead. I was angry about it at the time, but in retrospect I’m glad it happened. I cannot imagine thoughts of Jesse tainting this place now.

Benjamin made it a surprise. “Can you get someone to do the phones for a couple of nights?” he asked, casually, while we were doing laundry together. The townhouse in Charlestown had its own washer and dryer in a closet off the main bathroom. I probably would have loved the luxury more if I hadn’t been in the lamentable habit of paying my cleaning people to go and do my laundry in the past.

“Probably. Why?”

He shrugged, his head bent over the socks. “Why is it that they never match when they come out?” he asked rhetorically. “I don’t know, Abby, no reason. I’d like to get away and I know you could use it, too. You’ve been working really hard.”

I love it when people notice how hard I’m working. There’s a certain self-righteousness about working hard that only really works when people talk about how wonderful you are for doing it. I preened myself. “I suppose I have,” I acknowledged, modestly. “So what did you have in mind?”

He straightened up and looked at me. “What about Block Island?”

I didn’t ask how he knew about my infatuation with Block Island; Benjamin pays attention to everything. “I’d love to,” I said. It’s one thing to notice that I like the place and another thing altogether to invite me there. I was feeling a little awed. He was my knight in shining armor, after all.

“Great,” Benjamin said, happily unaware of his knighthood status. “I’ll call up the hotel. When do you want to go?”

“Anytime,” I said, automatically, then regrouped. “Well … what if I work Friday night and we go down Saturday, and stay through Monday. Could you manage that?” Probably not, I thought. He did have a profession, too. Sometimes I tend to forget that I live with somebody whois part of the nine-to-five world. He would probably say no and then we’d argue about whose work took precedence.

“Sure,” he said.

I swallowed the arguments I’d been preparing and meekly picked up the laundry basket.

If you ever go, stay at the Hotel Manisses. Though the name has always sounded Southern to me (“That’s Manisses, not Manassas, Abby,” Benjamin said), it’s actually a name given by the Narragansett tribe and means “island of the little god.” Very economical in their expression, the Narragansetts. The hotel is named for the island and is one of the Victorian old ladies, a little creaky and stuffy, but with its elegance still intact despite the need for a facelift and a tighter corset. Our room was named, in the unfortunate custom of the hotel, after a famous local shipwreck, the Palantine. It had a whirlpool, a nice post-Victorian touch. But the real attraction is the bar—cocktails extraordinaire, a view of the harbor, and a style that never goes out of style.

We had dinner reservations for seven, and at six headed down to the bar. I was thinking about blue drinks—I’ve always liked fancifully colored cocktails—but Benjamin had apparently made alternate arrangements in advance, and a bottle of Mumm’s was waiting for us.

“What’s this?” Okay, so I can be a little slow at times.

Benjamin and the bartender exchanged meaningful looks and the bartender popped the cork—discreetly into his hand—before pouring into the two waiting flutes. He was smiling broadly. I had the nagging feeling that I hadn’t zipped up my dress, or something equally embarrassing. “What?” I said again.

“This.” He opened the box before handing it to me. Okay, so I can be very slow. The solitaire glinted brightly against the blue velvet and, absurdly, there were tears in my eyes.

So maybe this particular madam is a romantic at heart after all.

Maybe being a romantic has something to do with the layers of rationalization that I used to go through on almost a daily basis.

There’s something that happens to you when you spend enough time watching people screw up their lives, when you are the conduit through which they earn money that they then spend on stuff that might kill them.

When I first started my agency, I didn’t think much about any of it. I was in complete denial about any downside there might be to the business. I was too high myself from the excitement of doing something forbidden, from the money and the success of the operation, and from my sudden and delightful status in Boston’s nightlife to think about much else. It was a very self-involved view of the world; but it’s a profession that encourages self-centrism, so it’s hard to think how I might have been successful if I’d felt any other way.

But as time passed and my priorities changed, doubts began to creep in. Doubts about whether I was as lily white and innocent as I told myself—with some frequency—that I was. Doubts about whether I could do what I did and still feel good about myself as a human being.

The reality is that I sent girls to places that I’d never want to go, to do things I’d never want to do, and that, given half a chance, I would do it all over again. Like everybody else, I was in it for the money. And the money was good enough to soothe my conscience for a very long time.

There are phases of justification that you go through. There’s the knowledge, in some cases the very sure knowledge, that if the girls didn’t work for me, they’d be working for someone else, and probably someone who would treat them far worse than I did. I knew enough about the other services in town, not to mention the street pimps, to know that I was the caviar of the escort world. So this worked pretty well for a while.

> Then there was the justification that involved my clientele. Ninety percent of my clients, as I’ve mentioned, are white-bread, vanilla-sex kinds of guys. They’re mostly guys that I’ve been sending women to for years and years. I know them, and as much as is possible in our little world, I trust them—or at least I trust myself to handle them. So if a girl came to work for me after working for one of the other services, I could rationalize that I was a step up for them, a step toward a better life. Once in a while, a girl would leave the job for something better. Once in a while she’d get past the patchy economics that had placed her in that position and move on, and I’d congratulate myself on having played a role in her success. This, I told myself, meant that I was doing something good.

Then, at some point, I just stopped rationalizing altogether.

These days? I don’t feel guilty about what I do, though I also don’t try and kid myself that I’m Mother Teresa. We all carry this kind of puritanical history with us in this country. This is the only place where it’s okay to watch someone being murdered on television, but you can’t show part of a nipple: that’s pretty screwed up. I enable two consenting adults to spend an hour together; he gets his jollies, she gets her money, and frankly I don’t see a whole lot that’s wrong with this.

I also don’t see a whole lot there to brag about, either. It’s a job. It’s always been a job. I just used to romanticize it to the point of parody, and somehow lost track of my own compass in doing so.

There’s something exciting about doing something illegal. There’s a whole concept in our society of the outlaw as being hip, romantic, and cool, and that’s how I saw myself: Outlaw Peach, sexy and seductive, clever and compassionate, the Belle of Boston. It got me through some difficult times and it got me past a whole lot of insecurity that I might not have shed otherwise.

Madam

Madam