- Home

- Jeannette Angell

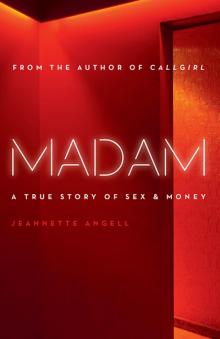

Madam Page 11

Madam Read online

Page 11

Home was, and has always been, Charleston, South Carolina. No matter how long I stayed in the North, that was where my roots were, where my persona came from. We were the eighth state to sign the Constitution and the first state to secede from the Union before the Civil War.

Even that wasn’t enough for Charlestonians, who do everything to excess: one small island south of Charleston said that if the state didn’t secede from the Union, then the island would secede from the state. That‘s the kind of people we are: opinionated and absolutely convinced that we’re right, no matter what. Whether it’s about our cuisine (heavy on okra, boiled peanuts, pork rinds, pimento cheese, and way too many peaches) or about our heritage (Rhett Butler, it is to be remembered, hailed from Charleston, and a number of rather famous pirates trolled off its coast), we’re passionate about who we are.

My mother certainly was. I have to give her that. There are only a handful of names in Charleston that matter—and she has one of them, her marriage to my father notwithstanding. Upon his death, she regained her own name, which I suspect she regretted ever having put aside.

She still lived in the Italianate house on South Battery Street where I was raised. It was both a dream and a nightmare to grow up in. The requisite southern verandahs, balustrades, and ornamentation looked better on a wedding cake than on a house.

I make fun of Charleston, but it made me who I am, and who I was until I left for Emerson College, Boston, and the pleasurable anonymity of a university town. I grew up surrounded by Meaning, with a capital M.

Not three blocks from where I grew up was Cabbage Row, renamed and celebrated in the musical Porgy and Bess as Catfish Row by George Gershwin when he moved to Charleston in 1934. I remember walking on Folly Beach when I was in my romantic teens, thinking of Gershwin and Heyward working only yards from where I was strolling, echoing what were then the neighborhood sounds—the butter bean man, the strawberry man, the fresh shrimp man. And the chuckle at the composer’s weakness for publicity when he tried to rename Folly Beach, recreate it in his own name as Gershwin Beach.

It didn’t work, of course; I told you that Charlestonians are stubborn.

I am the child of my past and I’m as stubborn as the best of them. Maybe that was why I was here: I wasn’t willing to let my mother, or my past, keep me from claiming my present. I had a life, a life that I loved; and my hometown was part of who I was. It was time for my past and my present to connect, for the circle to close. So it was my own stubbornness that had brought me here, the stubbornness of my people, the stubbornness of the marshes and the wind and the voices of Charleston’s past.

South of Charleston and all the way down to Savannah the coast is dotted with sandy barrier islands. Drive south from the city on Route 17 and the rivers are brown as tea. There’s a natural panorama that unfolds, slowly, enticingly: tall cypress trees and sturdy oaks, the palmetto plant that’s the state’s official flower (and why on earth do states need an official flower, anyway?), kudzu, yucca. The shore is fringed with grasses, tall stiff sharp ones that alone seem to be able to withstand the rages of nature.

Hurricanes whip up the coast, growl and worry at the barrier islands, and find shelter in Charleston. They’re the only untamed thing there, the only hint of wildness, the only time where being out of control is part of the city. Any number of hurricanes have left their mark–and their devastation–on Charleston. In 1989, Hugo ignored all conventions, roared through Charleston, and kept going inland all the way up to Charlotte. September and October have never been the same since, or so my mother asserts, as she talks to me on the telephone during those months, no doubt scanning the sky. If she isn’t fretting about something, my mother isn’t happy.

Fretting about me is and always has been one of her favorite pastimes. She fretted about my grades, my boyfriends, the hems on my skirts. Once I moved to Boston, she fretted that I wasn’t eating enough, that my laundry wasn’t done properly, that I was giving Siddhartha and Court the wrong brand of cat food.

Let alone what I was doing for a living.

She met me at the airport, brisk and moving quickly as usual. I’ve never been able to understand, much less imitate, my mother’s level of energy and action. “The car is parked over here. What do you have to carry? It’s good to see you, dear, and isn’t it cold?”

We sat in front of the tremendous fireplace in the living room of the Italianate house on South Battery. I was drinking a glass of chardonnay; my mother was doing what she called “catching up,” which meant sharing a year’s worth of local gossip with me. “Well, of course, we all knew when she married him that it would be a disaster, but she went through with it anyway. He didn’t have a name, don’t you know… .”

In Charleston, there are names and then there are Names, and my mother was definitely referring to the latter. They’re all Anglo-Saxon, of course, though nobody here would ever refer to them that way. They’re the Important People. Until she married my father, my mother bore one of those names.

She never regretted it, or so I’d like to think. In the dining room of the immense house that she shares now only with shadows and her memories, there is a sort of shrine to him: his portrait, painted by a celebrated Carolinian artist; a medal he had earned fighting in the Second World War; a clutter of framed photographs on the sideboard; the first present he ever gave her, an inscribed copy of Winnie-the-Pooh.

I pause at the shrine, touch the memories—but they belong to her, not to me. This was not what I held in my heart of my father. Just his scratchy whiskers on my cheek when he kissed me, the ever-present smell of pipe tobacco, that door that was shut on me while I waited in the hallway.

My mother has her own pipeline, it seems, to the uppercrust Brahmins of Boston society, and is more than a little disappointed that I have not taken my place among them. I bring up my catering business. She counters with the idea of going back to school. I reiterate my commitment to my business. “Maybe you think that catering is beneath me,” I say, provocatively.

She wrinkles her diminutive nose. “No one is accusing you of catering, dear,” she says, her hands delicate as she balances her teacup. The china is so fine it glows, translucently in the firelight. “That would indeed be beneath you.”

And so I learned that she knew, but I learned nothing else, for my mother is not one to confront, to look too hard or too closely at any of the parts of life she finds messy or inconvenient. Every little problem can be smoothed over with a smile; every major problem can be ignored. It was an approach that had served her well through all of her life, and she wasn’t about to give up on it now.

All the same, I was grumpy. Maybe I had really wanted a confrontation. My friend Tammy, who is a lesbian, told me once of her disappointment when she went home to break the news to her family. “I thought I’d shock them,” she said. “I thought they’d all be horrified, disown me, be embarrassed, something. But they took it so well. It was an amazing anticlimax to the whole ordeal.” Perhaps I was feeling the same way, daring my mother to force me to tell her what I was doing, trying to force her hand. I’m not even sure why. Maybe getting angry would have made me feel like I was, at long last, her equal.

Is any daughter ever her mother’s equal in her own mind?

Charleston did its usual Christmas thing, white holly berries on the doors, choirs singing in the streets, parties with hot mulled wine, all very Dickensian, and I found myself fading further and further away from it all. My mother and I decorated a tremendous Christmas tree that soared up two stories in our tiled foyer; friends of hers came to sip punch and hot buttered rum and talk about each other. On Christmas morning, we opened carefully selected presents. Mine was a silver locket that I wear to this day.

It wasn’t that it wasn’t beautiful; it was. It wasn’t that we weren’t getting along after our own superficial fashion. We were. But I was finally acknowledging that I simply didn’t belong there, and perhaps I hadn’t, in fact, for a very long time.

I got back to

Boston and sat in snarling traffic all the way through the Callahan-Sumner Tunnel from the airport into the city. The taxi driver was less than loquacious, and that was fine with me.

I was home.

In the end, you choose your family. Not the one you’re born with, that you’re tied to with a stranglehold of shared pasts and uncertain futures, but the people you choose to make your family.

I sat in my living room and looked at Robert and Luis and Jeannette and Lily and Benjamin, with Siddhartha and Court purring nearby, and I felt like purring, too. The ties that bound us all together were fragile—more fragile than any of us thought—but they were real, they were chosen, and they were conscious. And maybe, in the end, that’s all that anyone needs.

In one of Clannad’s songs there is a line that says: “As deep as you could wish to find / On the blind side of your heart / Safe inside your mind.” That’s where they all are: safe inside my mind.

Business and Family

Talking of how you describe your profession to people brings me nicely and emphatically back to the present.

Sam loves the park. What is it, is there something encoded into the DNA of every child at birth, that they’re drawn to these places of sand, swings, jungle gyms, and inane chatter? I can think of a lot of places, kid-friendly places, I’d rather go—a walk on the beach, an adventure on a farm, a trip on the river—but no, it’s the park, it’s always the park.

There’s something to be said, I suppose, for consistency.

When school is out, or on weekends, we go nearly every day that the weather is good. I bring a magazine and my cell phone, along with all the paraphernalia that goes with having children: sippy cups, a snack to hold him over, and of course Band-Aids.

Usually the magazine is ignored, since Sam appears to require my close attention to all of his feats, including the most mundane. “Look, Mom, watch me go down the slide!”

“I’m watching!”

“Mommy! Not fair! You didn’t see me!”

“I saw you, Sam, I saw you!”

“Mom! Watch me swing! Look how high I can go!”

“Very nice, dear.”

Such are our usual conversations. So I bring things with me, hoping that this will be the day when my child will magically develop some self-sufficiency and I can actually read. Never happens.

The cell phone, however, is a different story.

I talk with the other mommies, of course. And (to my initial and complete surprise) that’s an accepted category in which to find oneself—“Mommy.” We don’t talk about what we do outside of being a mother. We don’t even talk about our homes, our significant others, or anything that is unrelated to diapers and rashes and fevers.

We talk about our children.

Here, I don’t need to trot out my tired catering story. Being Sam’s mommy is quite enough for them.

We sit on a bench, the sun slanting down pleasantly through the trees, the kids all nicely occupied. Maybe one of them trips and needs a hug; maybe someone has harsh words with someone else; but that’s the extent of the potential disasters, the potential acrimony. Birds chirp overhead. I eat a few soggy animal crackers and pay attention to the conversation, which has to do with Marianne’s daughter’s teething problems.

And then my phone rings.

“Hello?”

“Hey, Peach. It’s Pete Povaklas.”

Oh, great. My best client from hell, and how does one disguise this particular conversation? “Hi, Pete,” I say, cautiously. The other mommies are still talking in the background, their voices politely muted so that I can carry on my conversation.

“Peach, I want someone new. I mean, really new. Someone who will appreciate me.”

If I were at home in my study right now I know what I’d say. I’d tell him that he would be appreciated a lot more if he treated the girls with a little more respect. It’s a conversation that we have on a semiregular basis. But in view of the circumstances … “Sure thing,” I say, noncommittally. “I’m not at my desk right now. Can you call me back later and we’ll take care of it then?”

Wishful thinking. “No, Peach,” he says irritably. “I’m tired of always talking about something later. All you ever say is, ‘We’ll talk about it later.’ I want to talk about it now. You used to have such great girls.”

He has a selective memory. He had been just as irritated in the supposed good old days, whatever they were in his little delusional world. “I still do, Pete,” I say casually, catching the eye of one of the mommies and flashing her a reassuring smile. Just a regular mother, here, trying to tell this guy that women don’t want to have sex with him because he has such an irritating personality. “I can look at the list when I get home, but I don’t have it with me right now.”

“List? What list?”

Oh, God, Peter, show a little initiative in the brain cells department. “Just a joke,” I say, lamely. How was I ever going to get this guy off the phone? “What I’m saying is that I’m out, I’m busy, and I’ll be happy to talk to you later, but I can’t now,” I say, more firmly. Sam is throwing sand out of the sandbox. That alone is a good reason to get off the line; it’s not an action destined to make me popular with anybody at the park.

“Peach, with you it’s always later—”

I cut him off, ruthlessly. “Well, it is now, Peter,” I say brightly. “Talk to you shortly.” I press the disconnect button and sigh, carefully not looking over at the cluster of mommies. Maybe they’d believe that I’m in real estate?

Some days, that sounds like a far, far better alternative.

I was going to have to make a decision about Benjamin.

After drifting casually in and out of the periphery of my life for nearly two years, he had finally decided that he needed more than a garage band and an occasional night in my apartment, which was, of course, very good indeed. Don’t get me wrong about that, I just wasn’t sure where, or even whether, I fit in with his new plans.

He stopped driving altogether, stopped working for the taxi company, stopped moonlighting as a driver for my service at night. He sat around my living room floor for several weeks surrounded by glossy brochures from various schools, frowning at them, muttering to himself. It would have been tremendously endearing if it hadn’t made me so nervous.

While I wasn’t altogether comfortable with my relationship with Benjamin, I feared losing it. What if whatever it was that he was looking for took him away from me?

So I tested him. I manufactured reasons to be angry with him. I drank and partied and ignored him for days on end, then attacked him, not listening to any kind of reason, finding myself in an insane-feeling groove where I was more invested in being angry than in fixing what was making me angry in the first place. Not the most pleasant of situations.

Benjamin put up with it all. He left when I threw things at him and came back after I had calmed down. He tinkered around the apartment, fixing things that he hadn’t had the time to get to for months. He made love to me slowly and tenderly and sweetly. He kept looking at the brochures.

Finally, he made up his mind, and enrolled at the famous North Bennet Street School in Boston’s Italian North End. North Bennet Street has an international reputation as a craftsman’s school, one of a vanishing breed. It’s been around since 1885, and the name alone commands respect. I’m not sure that there are too many names that do that anymore.

I was in awe. Here was someone I thought was going to spend the rest of his life drifting in and out of jobs, drifting in and out of bands, drifting in and out of me. Yet he was making decisions that were radically changing the course of his life.

Still, I was a little scared that once he did that, I wouldn’t have a place in his life anymore.

So I was fairly delighted when he asked me to go with him and visit the school.

Here you can learn piano technology, jewelry making, locksmithing, bookbinding, violin making and restoration, and—Benjamin’s choice—restoration carpentry. In an age of fast

food, fast sex, fast education, North Bennet stands out as the continuation of a long tradition of apprenticeship in crafts that may well disappear altogether if Wal-Mart has its way.

Or so Benjamin told me. I was still trying to catch up with his enthusiasm. Ideas I didn’t even know he had ever considered were tumbling out. He was going to bring back the beauty of old places. He had been looking around, he said, going on ghost hunts, looking at abandoned mills and tumbledown houses.

He wanted to bring life back into these buildings, and he wanted to do it right. He wanted to learn how.

I had underestimated him, had thought that Mnemonic and the Sunday afternoon football games were all that was going on in his world. I looked at the craftspeople at the North Bennet Street School, at their concentration, their joy, and their attention to detail. I looked at the answering light in Benjamin’s face, and I knew that something magical was happening here. Like Jen describing the early-morning masses of her childhood, I absolutely knew that the earth was moving, that something powerful and unique was being created, called into being inside him.

When Benjamin’s acceptance came through, I took him to Aquitaine in the St. Cloud building on Tremont Street to celebrate. We sat at a table with a pristine white tablecloth, drank very good wine, and ate far too much. As I looked at him over the rim of my wineglass, I had the sudden feeling that I was looking at a stranger, at someone I had never seen before.

I don’t mean that in a negative way. Au contraire, there was a certain frisson of excitement, a feeling like I could discover him all over again. It was an exciting feeling, and I entwined my fingers in his, seeing him as though on a first date.

A couple of his eyebrow hairs grew against the others, and I found that endearing. I sat gazing into his eyes, totally unconscious of movement around us, of diners coming and going, of the wind whipping up and down Tremont outside the restaurant, just sitting and drinking and falling in love with Benjamin.

Madam

Madam